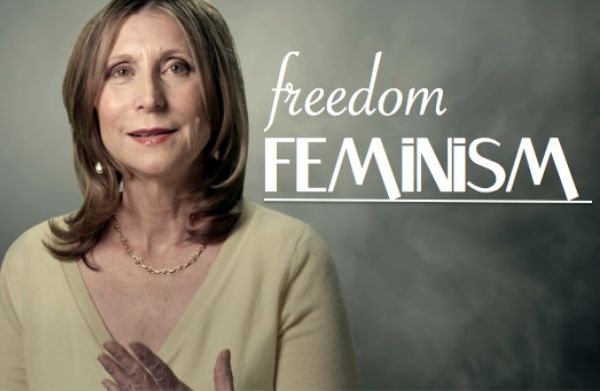

For those of us who roll our eyes whenever somebody asks if we identify with the word “feminist,” Christina Hoff Sommers’ new book Freedom Feminism: Its Surprising History and Why It Matters Today may make us change our minds.

Freedom Feminism is the bookend to Hoff Sommers’ 1994 classic Who Stole Feminism? How Women Betrayed Women, which showed how the feminist movement had been hijacked by anti-male, gender feminists. After reading Freedom Feminism, I think that what a lot of us who disdain the word “feminist” are reacting to is the stolen feminism.

Freedom Feminism is the bookend to Hoff Sommers’ 1994 classic Who Stole Feminism? How Women Betrayed Women, which showed how the feminist movement had been hijacked by anti-male, gender feminists. After reading Freedom Feminism, I think that what a lot of us who disdain the word “feminist” are reacting to is the stolen feminism.

We don’t want to be in the same boat as extremist law professor Catharine MacKinnon, Gloria Steinem, who famously said a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle, or Naomi Wolf, whose latest oeuvre is a biography of her vagina. Hoff Sommers sets the record straight in the new book: feminism started as a great movement that still has much to offer. Feminism, Hoff Sommers writes, “is one of the great chapters in the history of freedom.”

What I love about this book is that it tackles a big canvas—it starts with eighteenth century “foremothers”—and is clear and interesting. Hoff Sommers tracks two strains of feminism, egalitarian feminism, early personified by Mary Wollstonecraft, the first feminist philosopher, who believed that men and women are essentially the same, and maternal feminism, personified by Hannah More, a bluestocking, who recognized the differences but insisted upon equality.

Freedom feminism is a synthesis of both, affirming the dignity of women, yet asserting “that efforts to obliterate gender roles can be just as intolerant as efforts to maintain them.” I confess that I always regarded Wollstonecraft as an annoying precursor of the worst in modern feminism. Buy yesterday I read this in Freedom Feminism:

In the early 1990s, more than 200 years after the publication of Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman, Somali-born Dutch dissident Ayaan Hirsi Ali found herself struggling to discover ways to assert the rights of Muslim women. The contemporary feminist theory she read made little sense to her; it seemed irrelevant to the plight of women tyrannized by political Islam.

But after a copy of Vindication fell into her hands, Hirsi Ali writes of being “inspired by Mary Wollstonecraft, the pioneering feminist thinker who told women they had the same ability to reason as men and deserved the same rights.” Wollstonecraft has not been forgotten, she survives in history, and young women such as Hirsi Ali find her powerful and inspiring.

Hoff Sommers maintains that feminism is still important. In many parts of the world, the feminist revolution has not really begun. In the U.S., women still face challenges with personal, family, and work lives that men don’t. This book is a must-read for all of us who want the historical knowledge and philosophical grounding to think about these issues. Added bonus: it is just plain fun to read for us history buffs.

It will be hard at first, but I am giving some serious consideration to calling myself a feminist.