Amid the battle to end segregation and the chains of racial discrimination, Martin Luther King Jr. recognized the beauty and uniqueness of America's founding documents and their promise of liberty and justice for all.

Over the past few decades, it has become increasingly vogue for academics, Hollywood elites, and leftist autocrats — most recently Russian President Vladimir Putin — to disdain the idea that there is anything exceptional, beautiful, or uniquely good about the United States of America or its Constitution.

Unfortunately, this prevalent contempt for American political institutions and principles has cultivated alienation towards America both at home and abroad. It surely motivated President Obama when, while campaigning for office, he repeatedly pledged not to improve, redeem, or restore — but to "fundamentally trans(form) the United States of America."

One of the primary instigators for such irreverence is the charge that American institutions are incurably flawed because of their historical co-existence with racial injustice and inequality. For example, in 2011, the New York Times editorial boardvilified incoming House Republicans for appealing to the Constitution as the just basis for lawmaking authority by equating this appeal with a call to return to counting African Americans as three-fifths of a person.

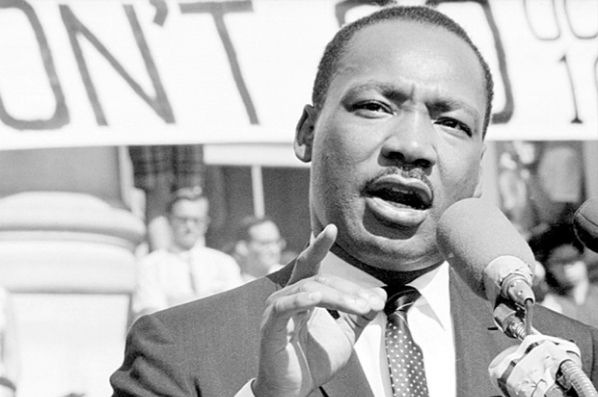

Like these modern day critics, Martin Luther King Jr. rightfully recognized racial discrimination as a tragic stain on our country's past. Yet, despite the injustices he and his people had endured, he still found reason to esteem and identify with America and its promise of liberty and justice for all.

In fact, as King spoke before thousands on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial a little over 50 years ago, he did not encourage despondency towards America nor a transformation of its founding institutions. Instead, he called for the nation to "live out the true meaning of its creed" that "all men are created equal." He reminded the country that "when the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir." This promise was that all men — black as well as white — "would be guaranteed the unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

In referring to both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, King recognized that these two documents are inextricably bound together and that only through the promise of the Declaration can we recognize the true spirit of the Constitution and the essence of the American dream. In other words, King understood — as did the Framers — that the compromises in the Constitution were an aberration from the principle aim of the Constitution: to secure individual rights and human freedom. On this basis, the Constitution always held the promise of justice for all regardless of race, and — through the ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments — the Constitution came into full harmony with the Declaration.

This is what makes America exceptional. In spite of its flaws, America was founded on the principle of universal human equality and freedom as announced in the Declaration and secured through the Constitution.

While Martin Luther King sought to improve the lives of the oppressed through a renewed dedication to the principles of liberty and justice for all, many of today's politicians increasingly appeal to class, gender and race to justify an ever-growing state, special privileges under the law and redistributive policies that promote cronyism and dependency, rather than opportunity and prosperity.

Although such politicians often claim to operate under the mantle of Martin Luther King, they have rejected the key principles for which he stood. Only through a continual re-dedication to our founding principles of liberty and equal justice can we ever hope to fulfill King's dream of an America where all individuals are free to pursue happiness and shape their own destiny.

Christina Villegas is a visiting fellow at the Independent Women's Forum. She is an adjunct professor at California State University, San Bernardino.