Why do so few women become the CEOs of major corporations, despite the tremendous gains women have made in terms of academic achievement and throughout the rest of the workforce? That’s a hot topic among social scientists and other researchers, and the New York Times’ Susan Chira is the latest to delve into it, with an article featuring stories from women who fell just short of that elusive corporate throne. Chira sums up her findings: “What their stories show is that in business, as in politics, women who aspire to power evoke far more resistance, both overt and subtle, than they expected would be the case by now.”

It’s important to listen to women who have had an insider’s view of the workings of our country’s most powerful corporations. Sexism, both overt and subtle, may help explain the dearth of female CEOs, and the public — and particularly industry leaders — ought to consider how stereotypes and assumptions about the necessary qualities for a good chief executive impact hiring decisions.

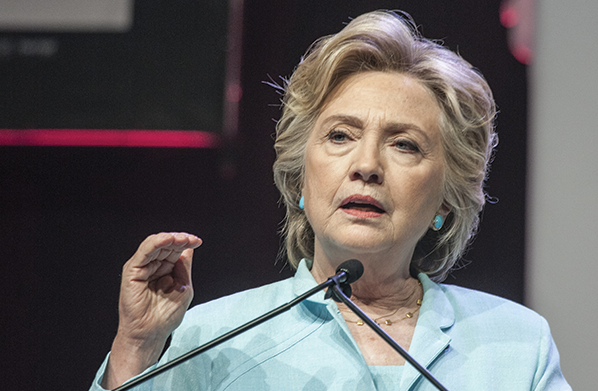

That’s why it’s too bad that researchers and reporters ended up politicizing this discussion. Rather than letting these female executives speak for themselves, Chira tries to tie them to Hillary Clinton, suggesting that the bias they might have faced was also at the root of Clinton’s loss in last year’s election:

The parallels with politics are striking. Research in both fields, including some conducted after Mrs. Clinton’s loss, has shown it’s harder for assertive, ambitious women to be seen as likable, and easier to conclude they lack some intangible, ill-defined quality of leadership. . . .

For her part, Mrs. Clinton is writing a book and speaking out more acidly than she allowed herself on the campaign trail. “Certainly, misogyny played a role” in her defeat, she told a rapt, partisan crowd at the Women in the World summit in April. She described what she saw as the thought bubble among some voters for President Trump: “He looks like somebody who’s been president before.”

The fury and revulsion aimed at Mrs. Clinton — as well as the more open misogyny in some quarters in the wake of the election — has led many women to question whether they’ve underestimated a visceral recoil against women taking power in any arena.

Many fear they already know the answer.

This claim needlessly alienates readers who didn’t support Mrs. Clinton’s candidacy for reasons that have nothing to do with her sex. Also, Chira undercuts her credibility: If she buys into the idea that sexism explains why Hillary Clinton lost, then I can’t help but wonder if she also cherry-picked the stories of the other women profiled in her article and guilelessly bought the sexism charge when there were other, more plausible explanations for why a woman didn’t become a CEO.

Some studies show that many voters have a bias for female candidates and are more likely to want to vote for a woman absent other information.

After all, while female politicians, including Mrs. Clinton, face unique challenges — such as a press corps that’s more likely to fixate on a female candidate’s appearance and family life than they would that of a male candidate — being a woman also has tremendous advantages. In Mrs. Clinton’s case, the Democratic National Committee did just about everything possible short of a full-on, Soviet-style election rigging to ensure that Mrs. Clinton won her party’s nomination. Why did they go to such lengths? A big part of it was the drive to shatter the glass ceiling and finally put a woman into the Oval Office. In fact, it’s hard to imagine that a candidate with Mrs. Clinton’s background and baggage would have been considered by her party if she hadn’t been a woman. For all the challenges that being a woman brings, it was also Clinton’s biggest asset and the foundation for her campaign.

Studies of people’s attitudes about female candidates are similarly mixed. Undoubtedly, there are plenty of disadvantages, such as challenges getting financing and accessing local political networks, but other studies show that many voters have a bias for female candidates and are more likely to want to vote for a woman absent other information.

Much like the constant use of wage gap statistics that dramatically overstate the differences between the earnings of men and women in similar jobs, the reluctance to acknowledge that sexism can work both ways complicates public discussions of these issues and undermines progress. That’s a shame. We should all want to live in a society that helps everyone fulfill his or her potential, which means we should take seriously the issue of how lingering stereotypes impact the workplace, particularly at the highest levels. That requires honest discussions and resisting the instinct to blame outcomes we don’t like — from statistical differences between men and women to election results — on sexism.