The Medicare Part D "donut hole" is a coverage gap in prescription drug coverage that for years has put beneficiaries on the hook for the full share of their drug costs. Basically, if your drug costs are low enough, they are either part of your deductible or are covered by your "plan sponsor" or insurance company, and if they are high enough, they are covered by the government via reinsurance (with some cost-sharing at every level). But if your drug costs are in the middle of these limits, you are in no man's land — the donut hole.

The Affordable Care Act, or ObamaCare, did try to address this: The law gradually manipulated the percentages that drugmakers, insurance companies, and Medicare beneficiaries in the coverage gap would pay, until ultimately, for all Medicare patients knew, the donut hole would be closed in 2020 and their cost-sharing would stay constant no matter what their drug costs (until they reached a very high amount, qualifying them as always for government help via reinsurance).

Closing the donut hole, for understandable reasons, is a very popular policy. No senior wants to fall into the donut hole — they'd be better off if it were closed. But as in all things in public policy, there's a right and a wrong way to reach this goal.

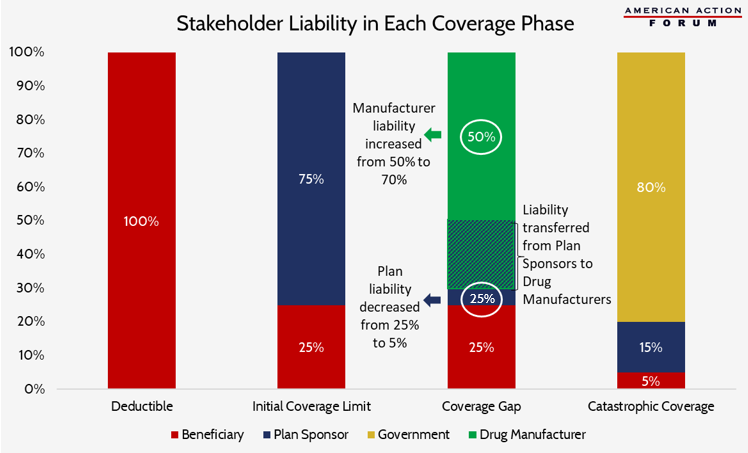

The latest budget deal under consideration on Capitol Hill has some bright spots — like repealing IPAB — but it also includes some moves in the wrong direction, like a change to how the donut hole is closed. Rather than splitting donut-hole costs between drugmakers and insurance companies 50 percent to 25 percent (with the remaining 25 percent coming from patients), the budget deal would move more costs onto drugmakers for a 70-percent-to-5-percent split.

In other words, the ACA would have forced drugmakers to pick up 50 percent of the cost of drugs in the donut hole. The new budget deal would force drugmakers to pay for 70 percent. This would reduce insurers' responsibility from 25 to 5 percent. Here's a helpful graphic from our friends at American Action Forum (AAF) that shows who pays for what in various parts of Medicare Part D. The blue and green portion in the third bar shows the policy provision that's currently under consideration.

Let's face it, it can be tempting to shrug off the government forcing new costs on drug companies. But there are risks involved with this policy approach. First, as Tara O'Neill at AAF points out, this could discourage insurance companies from taking an interest in reducing costs (when they are only responsible for 5 percent). Second, as I outlined in IWF's latest policy focus, government controls on how much drugmakers can charge can also have unintended consequences.

People might look at this convoluted mess and wonder why the donut hole exists in the first place. The answer is that it was primarily a budget gimmick in order to reduce the costs to the government (that heavily subsidizes Part D). The program shifted those costs on to Medicare patients (who, before Part D had neither "donut" nor "hole.") In their effort to continue to crunch budget numbers, lawmakers shouldn't make another misstep in foisting (an even higher share of) the costs of the donut hole onto drug companies when such a policy could harm patients by making critical drugs less accessible. Close the donut hole, sure, but do it the right way.