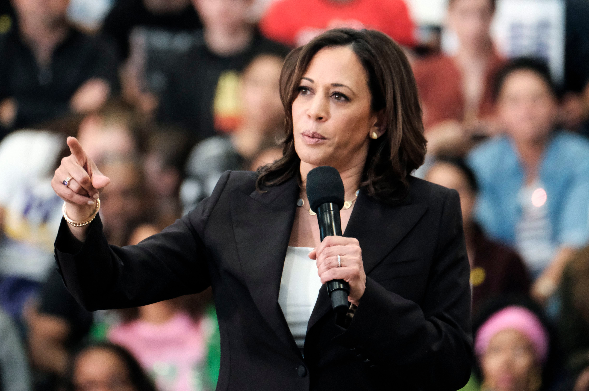

Last week, Senator Kamala Harris became the latest politician to peddle the wage-gap myth that American women earn only 80 cents for every dollar earned by a man. The California Democrat, who is running for president, has unveiled a plan to fine companies that cannot prove to the government’s satisfaction that they pay men and women the same amount for “the same kind of work.” The implication, of course, is that employers routinely discriminate against women in determining wages.

“It is just a fact,” Harris told MSNBC. “It’s not a debatable point.”

Actually, it is. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 already prohibits employers from paying men and women differently for the same jobs. And Title VII of the Civil Right Act of 1964 outlaws sex-based employment discrimination of any kind. (Notably, Massachusetts outlawed wage discrimination in 1945.)

As Harris no doubt knows, the 80-cents-on-the-dollar statistic is deliberately misleading. It is based on a raw comparison of the average yearly pay of all female workers and all male workers — irrespective of profession, job category, experience, training, college major, hours worked, or other relevant factors.

According to the Washington Free Beacon, a similar raw comparison of salaries in Harris’s own Senate office reveals that the senator’s female staffers make only 94 cents for every dollar earned by male staffers.

Does this gap mean that Harris is discriminating on the basis of sex? Of course not. As in the corporate world, wage disparities in Harris’s office are most likely the result of different job responsibilities, experience, and education levels.

If the comparison of male and female salaries in Harris’s office seems unfair, the nationwide comparison of men’s and women’s wages is even more so. National averages look not only at cushy congressional jobs, they lump together all jobs (blue collar, white collar, and everything in between).

But men and women are not equally represented in all fields. More men than women still choose careers in high-skill or high-risk industries such as plumbing, commercial fishing, mining, and law enforcement. And more women than men still choose careers in lower-skill or lower-risk industries such as child care and retail.

Even among college-educated workers, the so-called wage gap is a product of personal choice. More men than women still choose lucrative fields such as finance or engineering over teaching, social work, and nursing (professions that large numbers of women find appealing). This may well be changing, as more women migrate into business and engineering, and more men explore nontraditional fields, such as nursing.

But what shows little sign of changing anytime soon is that more women than men take time out of the workforce or go part-time to care for children. And studies show that even a relatively short time out of the workforce has a significant impact on earnings.

Even women who take minimal time off and return to work full-time after the birth or adoption of a child put in fewer hours, on average, than their male counterparts. This is true of professional mothers as well as blue-collar moms, who often turn down over-time opportunities that male-coworkers do not.

Parenting responsibilities, thus, account for a significant portion of the wage gap. In fact, studies that compare single childless women to single childless men, ages 35 to 43, have found that these women earn more — not less — than their male counterparts.

Unfortunately, employers will be less likely to offer flexible work arrangements if government regulators force them to pay employees who work from home or who work a reduced schedule the same as everyone else. (Although some sectors are friendly to off-site work arrangements, others still pay a premium for office face time.) A reduction in the number of flexible options would be bad not just for women, but for all employees who seek a better work-life balance.

The truth is that when studies that compare the earnings of similarly-situated men and women show a wage gap of only 2 percent (98 cents for every dollar earned by a man).

So why does Harris imply that the gap is so large and that the average employer deliberately pays women less than men? And why is she pushing a plan that pressures companies to eliminate flexible workplace arrangements?

In this era of identity politics, victimization is coin of the realm. Harris’s plan is a brazen attempt to convince women that she is their champion and to require further government intrusion into the private sector — a proposal that is likely to please the growing socialist wing of her party.

It is also a boon to the trial lawyers. That’s because Harris’s plan would ban arbitration for claims of pay discrimination, forcing employees claiming wage discrimination to seek redress from the EEOC or a federal court. Of course, federal agencies and courts move slowly. Litigation is costly. By contrast, arbitration is a lower-cost, more efficient, and often more successful way for workers to resolve employment claims — including wage disputes.

But Harris’s equal pay proposal isn’t really about helping employees. It is about pandering to special interest groups and ideologues who believe that the free market is itself sexist and that the government should guarantee equal outcomes (not just equal opportunity) in the private sector.