A basic underpinning of self-governance is fair, accessible rules of the road. When government decisions happen outside of an understandable process, Americans find little reason to buy into the outcome. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court’s decision not to take up Republican Party of Pennsylvania v. Boockvar leaves the rules governing our elections hazy, laying the groundwork for another contentious election cycle.

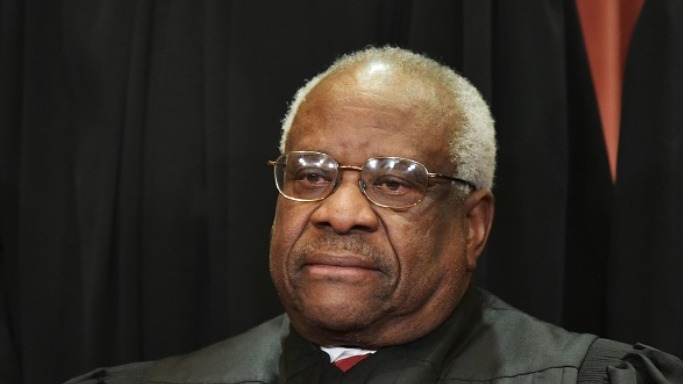

It is important to note at the outset that this case was not about whether the 2020 election was “stolen.” Justice Clarence Thomas, who dissented from the denial of certiorari, noted that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision did not alter the outcome of the election. But the case posed important issues for the legitimacy of our elections moving forward.

Boockvar was a case about the role of state legislatures in setting elections laws. Some facts: in 2019, the Pennsylvania Legislature decided to expand the availability of absentee ballots, but required ballots to be received by 8:00 PM on Election Day in order to be counted. The U.S. Constitution provides that “[e]ach State shall appoint” electors “in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct,” and the Pennsylvania Legislature has long exercised its wide authority to prescribe election rules. But, despite the Pennsylvania Legislature’s clear command, on September 17, 2020, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decided to extend that statutory deadline for three days, to preserve a “free and equal” election under the Pennsylvania Constitution.

On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court decided not to review this decision, leaving unresolved the question of whether state supreme courts—or Governors, or Secretaries of State—can rewrite elections laws. Justice Thomas dissented (as well as Justices Alito and Gorsuch in a related case), arguing the Supreme Court needed to address the issue.

“These cases provide us with an ideal opportunity to address just what authority nonlegislative officials have to set election rules, and to do so well before the next election cycle. The refusal to do so is inexplicable,” Justice Thomas wrote.

By failing to address this question now, Justice Thomas argued, the Supreme Court has risked undermining confidence in the fairness of elections moving forward. “If state officials have the authority they have claimed,” Justice Thomas wrote, “we need to make it clear. If not, we need to put an end to this practice now before the consequences become catastrophic.”

The Court’s refusal to take the case is concerning, though maybe not surprising. Certainly the Court decides issues outside of election cycles. Just last term, it decided challenges related to “faithless electors” deciding whether states could punish electors who vote differently from what their party asked for. But this particular brew of potentially toxic subjects—mail-in balloting, Donald Trump, unfair elections—may have discouraged the Justices from weighing in now. It is inevitable that such issues will arise in another election cycle, and we can only hope that the mess at that time will be manageable.

“By doing nothing, we invite further confusion and erosion of voter confidence,” Justice Thomas concluded. “Our fellow citizens deserve better and expect more of us.”