For decades, Boulder has been blaming the oil and natural gas sector for rising temperatures, cooling temperatures, the breakdown of roads, and now wildfires and the loss of snowpack. The city has even passed legislation to combat global warming. No, global cooling. Now, it’s climate change.

That’s why no one is surprised the epicenter of the east California movement, the city and county of Boulder, is leading the charge in the latest climate lawsuit against ExxonMobil and Suncorp Energy, and that San Miguel County, home to the mountain west’s Hollywood, is the accompanying plaintiff in the suit.

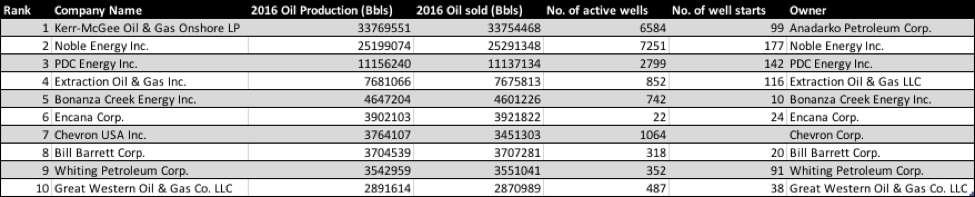

However, their choice of defendants Exxon Mobil and Suncor Energy is a bit curious. While Suncor operates the state’s largest refinery, Exxon’s financial footprint in Colorado is relatively small compared to other producers. In fact, Exxon doesn’t even make the state’s top-ten production list (See the chart below).

However, globally, Exxon is far larger than any of Colorado’s top producers. At the close of 2017, it had nearly 70,000 employees, while Noble Energy and Anadarko Petroleum had a combined total of 6,700 employees.

According to Forbes, Exxon is the second largest publicly owned oil and natural gas company in the world. And in 2017, it produced 4 million net oil-equivalent barrels per day and earned $13.4 billion off of its upstream businesses alone.

Its subsidiary, XTO Energy, operates in three counties in Colorado, but employs under 300 people. In 2015, Exxon and XTO together paid $8.3 million in taxes to Colorado and “invested more than $1.3 million in higher education, medical care, environmental research, and arts and civic organizations” in the state.

The plaintiffs’ chief claim against the giant is that Exxon knew it was contributing to climate change but continued to carelessly operate anyway. Boulder County’s website states that the companies “deceived the public and policymakers for decades about the truth so they could keep making billions of dollars.”

By suing Exxon, Boulder isn’t staking out any new territory. The oil and gas giant has been named in other lawsuits that have since been dismissed. It’s also the subject of an entire social media campaign #ExxonKnew that wound up being part of a coordinated effort to discredit the company, funded, in part, by the Rockefellar family. It’s also Rockefellar donations that are “the key to keeping the climate change lawsuits afloat” including the Boulder suit.

Canada-based Suncor Energy, the other defendant, hasn’t been in Colorado very long. It bought refineries from ConocoPhillips in 2003 and Valero in 2005 and combined them into a single operation in Commerce City. I drive by it several times each week on my way to and from work. It may not provide the majestic backdrop like the Rocky Mountains, but it does represent economic activity that helps fuel our 21st century economy.

Suncor refines 98,000 barrels of oil per day, turning them into gasoline and diesel fuel. It’s also a major supplier of jet fuel to Denver International Airport, and it is Colorado’s primary producer of paving-grade asphalt. Last year, the company reported earnings of $4.5 billion and produced 685,300 barrels of oil equivalent per day. In terms of refinery capacity, Suncor’s Colorado operation is fairly small when compared with other US refineries.

The company recently completed $445 million in environmental upgrades to meet clean fuel regulations.

The plaintiffs claim they don’t want to halt Colorado’s natural gas and oil operations, which may explain why they chose companies that don’t have huge financial footprints in Colorado. But they do want a jury a trial. Those aren’t cheap. Which is why it seems likely that those funding these lawsuits may have a say in who the defendants are. If that’s the case, then the choice of Exxon as a defendant doesn’t seem curious at all.