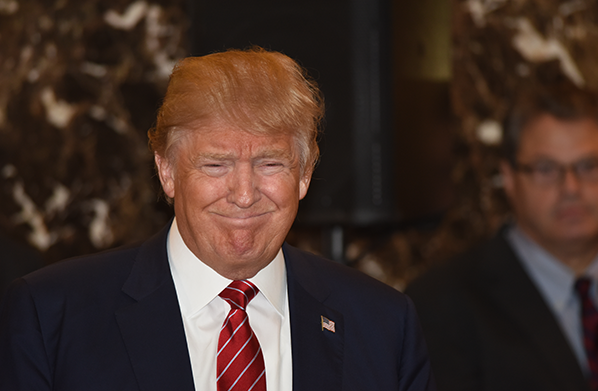

On Wednesday, the President signed an Executive Order requiring the Department of Interior to conduct a review of the last twenty-one years’ worth of designations under the Antiquities Act of 1906. While some environmentalists are up in arms, complaining that the President is trying to sell off sensitive public lands to the highest bidder, nothing could be further from the truth. The Order is a win for the rule of law.

The Antiquities Act is a product of a different time when “pot hunters” raided Native American dwelling and burial sites. The Act put a much needed stop to such practices, criminalizing the unauthorized excavation or appropriation of any ancient ruin or object of antiquity. It also allowed the President to designate as national monuments “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest.”

Despite environmental activists concerns, the Antiquities Act is not the most important statute for protecting environmentally sensitive lands. Far from it. It’s just the statute that comes without procedural protections and checks and balances.

Today, a number of federal (and state) statutes protect the United States’ important interests in historical sites and environmentally sensitive federal lands and waters. The National Park Service Organic Act requires the preservation of “scenery,” “natural and historic objects,” and “wildlife” on federal land. The Wilderness Act preserves the “wilderness character” of large tracts of federal land. Most importantly, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act comprehensively addresses the management of public lands. It directs the Department of Interior to preserve sensitive federal lands—those that have important scientific, historical, scenic, archeological and environmental values. It also allows the Secretary of the Interior to act on an emergency basis, protecting sensitive areas without public input for several years.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 stands alone among environmental preservation statutes, because it allows a President unilaterally to set aside millions of acres of land and water for special protections. In stark contrast to all of these other federal laws, the Antiquities Act affords zero procedural protections for those in affected areas. Modern statutes require public notice and comment, and many require Congress to approve of land withdrawals, but not the Antiquities Act.

The preservation of historic lands and procedural protections for the affected communities are both significant. Yet local communities are often surprised by the designation of a national monument. Consider one of the monuments that will undergo review under President Trump’s Executive Order: the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. This particular monument spans nearly 1.9 million acres. Its designation came with significant economic downside, halting mining operations that would have provided much needed income to rural Utah communities. Yet President Clinton gave the Utah Governor and its congressional delegation only 24-hour’s notice before publicly announcing the designation of the national monument—from a different state.

The irony about the Antiquities Act is that it was only ever intended to preserve small parcels of land in conjunction with a historic or scientific object. The text of the Act imposes two limits. First, the Act limits presidential authority to specific “objects” of historical or scientific interest. Second, it limits the executive’s authority over adjacent land “to the smallest area compatible” with the protection of said object. Indeed, the bill’s sponsor, U.S. Rep. John F. Lacey, rejected out-of-hand — “Certainly not” — the now-prophetic suggestion that the Antiquities Act might be used to tie up “seventy or eighty million acres of land.”

Despite these textual limitations, the Supreme Court has endorsed nearly unfettered presidential discretion under the Antiquities Act. The text cannot be interpreted so capaciously, but since the Court has declined substantively to review any monument designation for size or scope, abuses of the Act continue to go unchecked.

There is no question that Congress can reverse a monument designation — and has done so in egregious circumstances. And a number of monuments have also been retroactively modified. President Trump’s Executive Order signals that he is willing to reconsider monuments against the textual limitations of the Antiquities Act. That is a win for proper procedure and for good government.

Erin Hawley is a legal fellow at the Independent Women's Forum, an associate professor of law at the University of Missouri, and a former clerk to Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.